Paper presented to the Chinese Christian Scholar Association in North America,

July 1-2, 2008

My presence here among you might be somewhat of an anomaly. I am not American, and thus have little or nothing to say on cultural exchange between China and the United States. Nor am I knowledgeable on China, or on its relationship with France, my own country. I can only pretend to hold the titles of “cultural amateur” and “apologist-to-be,” and as such I present myself before you today.

Culture, History, and the Exchange of Virtues.

Reflections on Solzhenitsyn’s Harvard Address, June 8, 1978

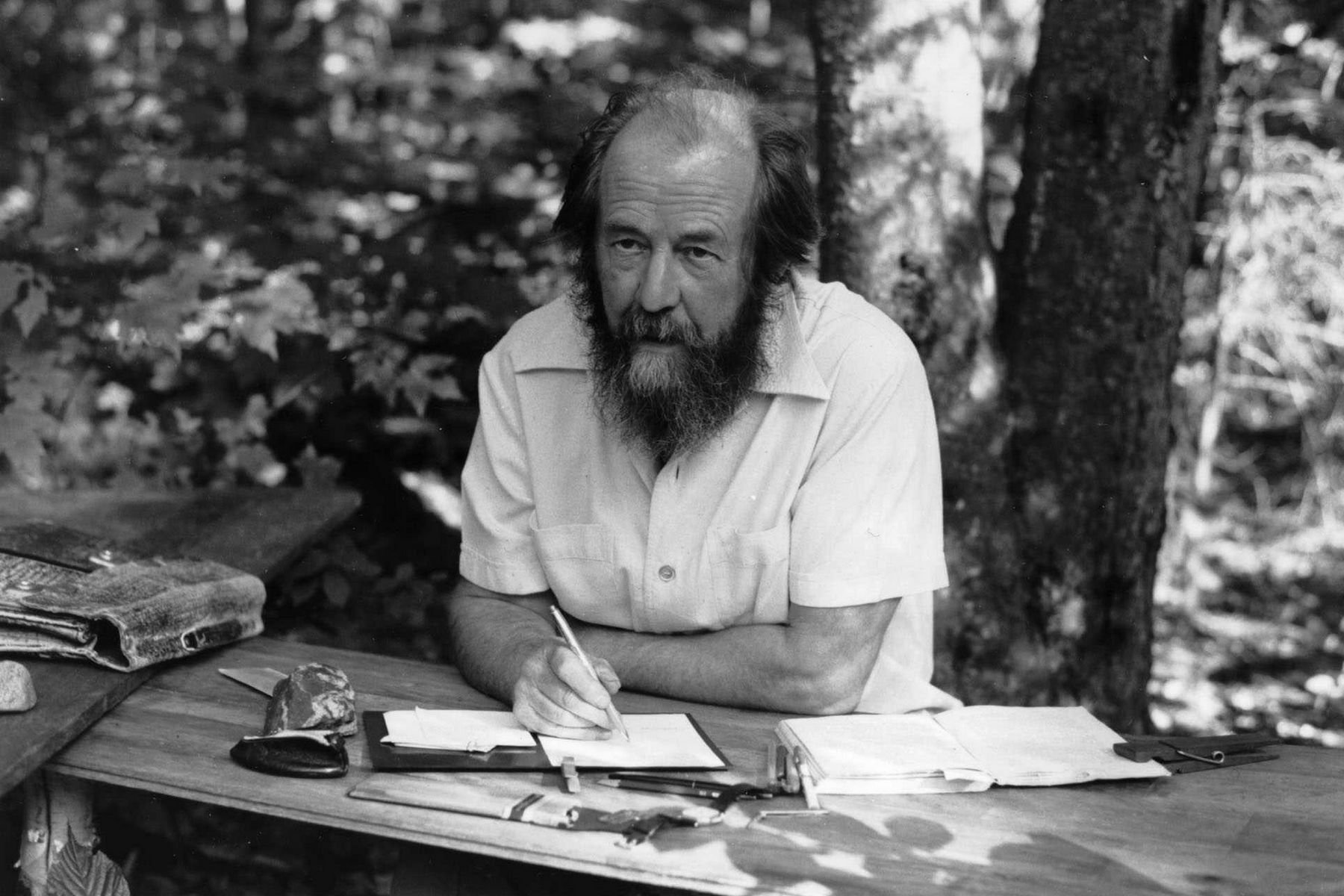

As a theologian in training, I come with a specific theological question, which is: “What is involved in the expression cultural exchange”? What is, precisely, exchanged through cultural interaction? Thus, my purpose is not to talk about what “cultural exchange” will look like in the twenty-first century. What I intend to do is to investigate the unseen foundations of what “cultural exchange” is. I intend to look with you at the implications, and, if I may say, at the dangers of cultural exchange. To reach a moderate success in this endeavor, I will invite to join us a Russian writer, cultural analyst, and 1970 Nobel Prize in Literature, Aleksandr Isayevich Solzhenitsyn. If it seems unusual that I have chosen this author, it is because this conference marks, almost to the day, the thirtieth anniversary of his Harvard Address at the 1978 Commencement. Moreover, this year is also Solzhenitsyn’s ninetieth birthday, and it seems fitting to take him as our guide today.

The Harvard Address: culture and virtues

Indeed, Solzhenitsyn is relevant to our subject because of his analysis of Western cultures and societies. In the first place, let me briefly summarize the main points of his Harvard Address. His initial observation is that the world is “split apart” between Western and Eastern (Communist) Europe. In his opinion the split is such as it has never been before. But more than the reasons of this split, he is concerned with the reasons for this continuing condition. Confronted with the rise of Eastern Communist Europe, he argued that the West has become passive, that it has lost its courage, its will-power, and more than anything else, its moral foundation. This is the consequence of the characteristics of modern Western cultures I now turn to.

Solzhenitsyn first attack the radical individualistic and materialistic world and ideology of the Western states, focusing all their energies on “well being,” at the expense of any other consideration. Faced with the challenges of economic depression, lack of national identity and social paralysis, the West finds refuge in blinded materialism. This finds it origin in the very foundation of modern Western states:

When the modern Western States were created, the following principle was proclaimed: governments are meant to serve man, and man lives to be free to pursue happiness.

The problem of having done so, he concludes, is that well-being has become the end, the sole goal and purpose of human life in the West.

One factor promoting unlimited well-being is what Solzhenitsyn calls “fashion in thinking.” To support his point he took the example of scientific research. Scientists, argues Solzhenitsyn, are not less free in Eastern Europe than they are in Western Europe or in America. We cannot realize the whole weight of this assertion when it was pronounced in 1978 Harvard. He asserted that, in fact, science does not advance scientific knowledge, but rather profit and economy, that is, a new form of Utilitarianism. Solzhenitsyn goes even further in maintaining that “[l]egally your [our] researchers are free, but they are conditioned by the fashion of the day.” What conditions one’s commitment is not scientific curiosity, nor the quest for good, truth, beauty, or aesthetic pleasure, but merely the dominant trend. Fashion. To belong “in” a culture, means just knowing about the latest fashion, regardless of what this fashion really means or says. When a culture is built upon such priorities as profit or fashion, so will cultural exchange. And in this case the value of cultural relationships can be questioned.

The unbalanced emphasis on well-being further leads Solzhenitsyn to criticize the modern idea of freedom that came to pervert a more comprehensive one. To be fair, Solzhenitsyn criticizes the direction freedom has taken, rather than freedom per se.

In fact, if a society is built on individual well-being, this same culture will eventually promote boundless individual freedom. What Solzhenitsyn saw here was the destructive nature of modern Western freedom. True freedom, he argues, is only meaningful when it is considered in its action against evil; but modern freedom is the freedom of doing evil at the expense of everything else. For Solzhenitsyn, “[d]estructive and irresponsible freedom has been granted boundless space,” and it becomes merely the freedom of evil:

Such a tilt of freedom in the direction of evil has come about gradually but it was evidently born primarily out of a humanistic and benevolent concept according to which there is no evil inherent to human nature; the world belongs to mankind and all the defects of life are caused by wrong social systems which must be corrected.

Here he points at a very important theological element. Culture is of the same nature as humankind: it is fallen. Evil is inherent to humankind and is thus an integral part of human culture. This direction for evil needs to be checked and “corrected” by virtues. Cultures must be sanctified.

If modern freedom favors deeds of evil, there is, according to Solzhenitsyn, another paradoxical aspect of the West that reinforces his previous conclusions, that is, a legalistic life. At first sight, it is difficult to reconcile unbound freedom and legalism. But the gap between these two notions is bridged when we realize that:

The limits of human rights and righteousness are determined by a system of laws; such limits are very broad […] If one is right from a legal point of view, nothing more is required, nobody may mention that one could still not be entirely right, and urge self-restraint, a willingness to renounce such legal rights, sacrifice and selfless risk: it would sound simply absurd. One almost never sees voluntary self-restraint.

What society and culture have declared to be legal is the last word on everything. Again, concerns about truth, the good, or other people, do not belong to modern societies. This view of freedom, based solely on its legal aspect can be called legalistic freedom. We often consider a legalistic life to be one without freedom, but if we follow Solzhenitsyn, it is also one of unbound freedom, as he said

[…] a society without any objective legal scale is a terrible one indeed. But a society with no other scale but the legal one is not quite worthy of man either.

For the Russian, both Western and Eastern societies are legalistic cultures that only lead to either restricted or unbound freedom. But both are without true freedom. Both have lost their virtues. The successive and interrelated themes of well-being, freedom, and legalism, lead us closer to the essence of Solzhenitsyn’s criticism of Western societies and cultures, which is, the lack of “moral criteria,” and the loss of the moral nature of Western societies and cultures. Such is the picture Solzhenitsyn painted thirty years ago.

Culture and the exchange of virtues

Our initial observation is that the foundation of modern societies and cultures are philosophical and historical, being the product of human history and thought. As Henry R. Van Til said, “Culture receives its meaning from the meaning of history.” If the meaning of culture is related to the meaning of history, it is therefore a theological issue as well. Indeed theology cannot be separated from the question of the nature and meaning of history. Moreover, we need to remember that the English terms “cultivation, “culture,” and “worship” all come from the same etymological family that includes cultus, culo, culero. Culture influences and is influenced by the history of its ideas, the history of its people, of its political relations, and also of its religion(s). Cultures always stand for the specificities of a history and a people. Cultures originate from the people of a country and thus are informed by the way of life, and by the character of the people.

Solzhenitsyn’s thesis is that all cultures are founded upon moral criteria, that moral foundations are necessary for a society and a culture to survive. Therefore, before looking at the possibility and merits of “cultural exchange,” we need first to understand what is implied and presupposed in such an exchange, that is, their philosophical and theological foundations. As I have said, cultures share the same foundations as humankind, which is, human nature itself. Cultures reflect human nature as well as the development of human societies. Therefore, a culture will always reflect the specific elements of its human nature.

We now come to what is involved in inter-cultural relationships. If Solzhenitsyn’s analysis of the nature of Western societies is correct, as I think it is, cultural exchange with the West implies the transfer, in part, or total, conscious or unconscious, of their nature. True as this conclusion goes, we need to remember that “moral criteria,” is itself an ambiguous term to use. The expression “moral criteria,” does not explain where these criteria come from. If all cultures have philosophical and theological foundations, their moral criteria also have certain foundations. For the benefit of our discussion today, I suggest that we use the term “virtue” instead of moral criteria, because it implies that our lives are connected to the nature of who God is.

Addressing myself to you as a theologian, I would say that “cultural exchange” should be about the communication of Christian virtues. Of course even a rapid glance at the world shows us that such is not the case, and that no culture is totally virtuous. However this has been the pretension of the so-called “Christian” cultures. The assumption that one’s culture is “Christian,” is one of the more common and damageable assumptions in Christian history. The relation between Christians has often been conditioned by the relationship between God and culture. Richard Niebuhr, in presenting the relationship between Christ and culture according to five main categories, has provided a well-known framework to the understanding of culture. However, I think that a main problem in his analysis of the five categories is the constant dichotomy drawn between Christ and culture, between God and his action in human history. Culture here is considered to be independent from God, as having a life of its own outside God’s activity in human history and in culture. Instead, one should maintain that all cultures are in relation to God, whether they acknowledge him or reject him.

This leads us to the next point, which is the parallelism between the relationship of “culture” to God and the relationship of humankind to God. This has important theological implications that cannot be underestimated. In Romans 1.18-32, Paul first affirms that we all know God: “For although they [we] knew God, they [we] did not honor him as God or give thanks to him […]” Paul is not arguing that we all have the sense of a divine power, or of a vague spiritual power. He is affirming that we know God’s nature, by virtue of creation:

For his invisible attributes, namely, his eternal power and divine nature, have been clearly perceived, ever since the creation of the world, in the things that have been made. So they are without excuse.

If we all know God, it remains true that some know God and reject him, while others know God and love him. Moreover, Paul is affirming that all people are in an ethical relationship to him, whether in communion or rebellion to him. We all are either in loving or rebelling relationship to God. Psalm 19 reinforces the same point: God is known through his creation.

But from the reading of this psalm, the question soon arises of how the works of God are visible to humankind. The first Jesuit missionaries entering China built their answer upon Catholic natural theology and affirmed that God could be demonstrated from nature, because of man’s natural abilities. Reformed theologians have given another answer and affirmed that God is known in nature, not because he could be deduced from it, but because the knowledge of him is structurally implanted in all creation. If this reading of Romans 1 and Psalms 19 is correct, it provides the basis for understanding the relationship between God and cultures, and a more comprehensive view of cultural relationship between Christians (and/or non Christians). From what I have said so far, we can conclude that the structure of our cultural life itself belongs to the act of creation, and therefore, that there is an unbreakable bond between God and all cultures.

Another question we are confronted with is the manner of God’s working in cultures, and history. Given the fallen nature of the world we live in, how are we to explain the presence of any good in cultures and history? Indeed, if the world is fallen, should not all good be absent of our world? We need, however, to note that even in a fallen world, God’s presence and grace are at work. This is what we call God’s common grace. This grace, a general benevolence of God towards mankind, gives the possibility for all people to bring about good into human societies and cultures, even though many live in broken communion with God. As theologian Herman Bavinck said, “[…] there exists […] a generalis gratia which dispenses to all men various gifts.” This common grace that God bestows upon all creation is the divine activity directing the general knowledge of God I just mentioned. The two meet at the intersecting point of culture and history. It is when we observe human cultures and history that we can more clearly see God at work through the knowledge he gave to all humankind. In the same manner that God brings history and his sovereignty together, so God’s common grace brings culture and history together.

Now, if we apply what we have just said to “culture,” we can conclude that any given culture is by definition in an ethical relationship to God. Since we all have a knowledge of God, all cultures are in relation to God due to their human-made nature. We can say, secondly, that the activity of God’s common grace in culture leads us to an understanding of the activity of God within culture. If we all know God then, in the same manner, all cultures reflect a knowledge of God. These two principles help us understand what the relation of culture to Christians is, and what the relation of culture to God is. Because each culture stands historically in ethical relationship to God, it means that each culture can be sanctified and be brought closer to reflect God’s nature. Since God implanted a knowledge of his nature in man at creation, cultures reflect this knowledge: a distorted knowledge, but a knowledge still. This nature of common grace is related to saving grace. If common grace touches the whole nature of the universe, so does saving grace. This rejoins Calvin’s notion of fides salvificans, a faith that regenerates the whole of man, and touches all of man’s activities. There is then no dichotomy between man and his works, between man and culture. Both man and culture are in need of faith and sanctification.

In terms of understanding what “cultural exchange” is, we need to remark that this implies the use of two categories: originating culture, and receiving culture. Few comments on these two categories are necessary. First, there is no passive culture in the process of cultural relations. Each culture is both originating and receiving, but never passive. The originating culture is not passive in the exchange because, in being transferred to another culture, it has a multi-level impact. On the other hand, the receiving culture is not passive either. The receiving culture should always evaluate the elements of the originating culture. Our responsibility as leaders and scholars is to help unveil the hidden foundations of cultural relationships, and the nature of cultural exchange. A culture living out of respect and understanding of the past can be a fertile ground for the Gospel, more than a culture focused on the present moment can be. A culture founded on humility can teach you something about how to relate with another culture. But in the case of a culture founded on grand arrogance in one’s own rights, the exchange will certainly lead to the downfall of the receptive culture. We could go on an on and multiply the examples, but this is not necessary for an understanding of the matter.

We do not have time now for a summary of what the cultural exchanges between France and China have been. Let me just say that the past twenty years have seen France and China coming closer together. Along these lines, they have tried to promote inter-cultural engagement. For example, the “Chinese culture year” organized in France in 2004 was a great success but revealed a motivation centered on economic needs. A year supposed to promote cultural understanding and exchange eventually turned out to be merely one of selfish interests. One thing that demonstrated this conclusion is the ban put on Chinese Literature Nobel Prize winner 高行健 (Gāo Xíngjiàn) to participate to official celebrations. Our motivation is also an aspect of cultural engagement that we need to help “sanctify.” Cultural engagement should not be motivated by mere economic needs but by a desire for mutual understanding, by a promotion of humility and love. It should include, if we read Galatians 5 into our theme of cultural relationships, love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, goodness, faithfulness, gentleness, and the “mastering of oneself.”

From this perspective then, cultural engagement demands two things. First, it encourages us to see which elements of the receptive and originating culture are in need of sanctification. It also demands for us to be specifically aware of the characteristics of Western societies Solzhenitsyn mentioned, because this is what will be transferred in the process of cultural exchange.

Conclusion(s)

It is now more than time for me to conclude. First as a mere reminder, let me say that cultural exchange implies the exchange of values, virtues, and vices. As we saw with Solzhenitsyn, all the negative characteristics of modern Western societies are involved in cultural transfer. But their counterpart, the virtues corresponding, should be part of the cultural exchange as well. Secondly, and this is an exhortation to us all, we need to promote an awareness of what the foundations of our cultures are. This demands an understanding of what our cultures are in the face of God. This is a way through which we can cultivate God’s common grace and sanctification in our cultures. Only then will we be able to avoid the plague of cultural superiority, by seeing all cultures through the eyes of the one who created them.

“Exchange” does not merely involve the artistic, technological, or economic aspects of our cultures, but rather the very soul of culture. The soul of a culture is the soul of man. The nature of a culture is the nature of man: fallen and in need of being sanctified. Cultural exchange is an ethical exchange before the eye of God. As Solzhenitsyn concluded thirty years ago: “[…] man’s sense of responsibility to God and society grew dimmer and dimmer.” This is true, but we can go beyond this negative conclusion and say with Reformed theologian Herman Bavinck that:

Although for man’s sake the whole of nature is subject to vanity, nevertheless nature is upheld by the hope which God implanted in its heart. There is no part of the world in which some spark of the divine glory does not glimmer.

If it is so, our responsibility is to make cultural exchange meaningful before God, that is, we need to bring forward the cultural elements in which the divine glory does glimmer, and thus work towards the sanctification of all our cultures.